How It All Started – The Courage to Speak®

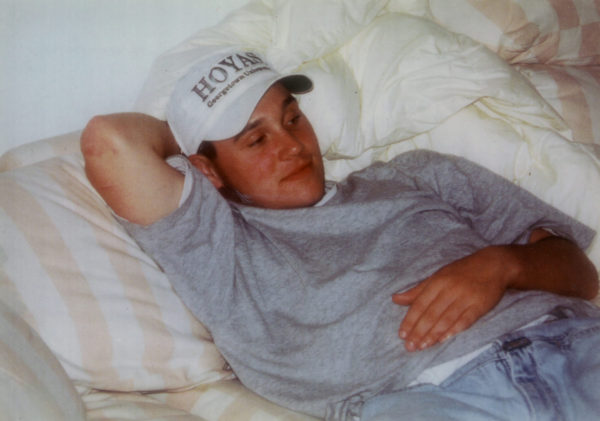

On a day like today, I remember my beloved son, Ian James Eaccarino, whose life was tragically taken from us far too soon. It’s hard to fathom how many years have passed since that moment—since my life shattered into a million pieces.

There are no words to fully describe the devastation of losing your child. It’s like waking up every day, only to find the world is darker, emptier, and somehow crueler than you remembered. Ian was just 20 years old. He had his entire life ahead of him, a life he would never get to live.

He was my beloved boy—funny, kind-hearted, but hiding struggles that I didn’t fully see because he kept them secret.

I remember the morning like it was yesterday. The sun hadn’t yet risen, but I had—ready for what should have been another normal day. I heard the TV playing very loud downstairs from his room, so I went to turn it off and wake Ian, but instead, I found him warm, lifeless in his bed. His body, so familiar, so mine, was still. I screamed for Larry, but in my heart, I already knew. My son was gone. His struggle with drugs had claimed him just one day before he was supposed to start recovery. One day. Just one more day, and maybe he would still be here. But there is no rewinding time, no undoing the nightmare of that morning.

That night, before Ian’s funeral, I lay in bed, numb, staring at the ceiling, wondering how I could possibly face a room full of people. How could I stand there and talk about my son, my sweet boy, without breaking apart completely? My husband was asleep beside me, but I shook him awake. “I can’t do this,” I told him. “I can’t say goodbye.” I was choking on the words, on the truth.

But then I realized I wasn’t just saying goodbye to Ian. I was saying goodbye to the silence. I was saying goodbye to the shame, the hiding, the pretending that everything was fine. Ian’s death couldn’t be in vain. His story had to be told, no matter how much it hurt me to tell it.

Weeks later, at St. Thomas the Apostle, I stood before his friends, his teachers, those who loved him, and the community, and I spoke. My hands shook, my voice cracked, and my heart felt like it might stop right there, but I spoke. I told them how addiction had stolen my son. How drugs had seeped into his life, slowly at first, then all at once, until they took everything. I told them about the Ian I knew—the boy who loved animals, who laughed with his whole heart, who deserved so much more than what addiction gave him.

And in that moment, I knew—I couldn’t keep Ian’s story to myself. I couldn’t bury it with him.

Since Ian’s death, I’ve dedicated my life to speaking out, to warning parents, to educating youth. But every time I stand in front of a crowd, I feel the weight of Ian’s absence. Every time I tell his story, I feel the sharp sting of what could have been—what should have been. My son should have grown up. He should have fallen in love, had children of his own, lived a full life. But instead, I am left to carry his memory, to fight in his name, to scream into the void that addiction is real, that it steals our children, and that we must do something before it’s too late.

I want to thank each of you for your continued support of our mission. By standing together and speaking out, we are making a difference. Please join us in remembering Ian and supporting the Courage to Speak® Foundation, so that no other family must experience the pain we’ve endured.

Together, we can empower youth to live drug-free lives and encourage families to communicate openly about the dangers of drugs..

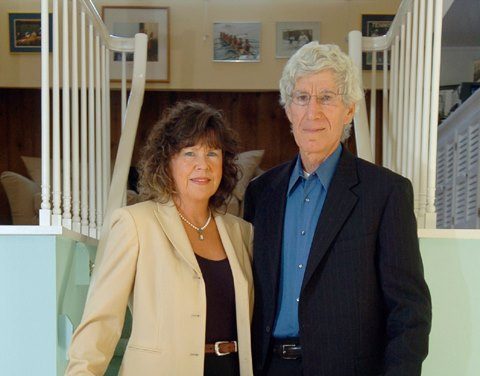

The Courage to Speak® Foundation is a nonprofit organization based in Norwalk, Connecticut, founded by Ginger and Larry Katz after the loss of their son, Ian, to a drug overdose. Their mission is saving lives by empowering youth to be drug-free and encouraging parents to communicate effectively with their children about the dangers of drugs.

Since its founding, Ginger Katz has reached hundreds of thousands through nearly 1,000 presentations. The Foundation offers prevention programs for elementary, middle, and high school students, along with the Courage to Speak – Courageous Parenting 101® program for parents. Ginger is also the author of Sunny’s Story, a book for children and families.

Learn more at www.couragetospeak.org.